A new chapter has opened in the story of Frida Kahlo’s legacy, and it brings with it a wave of unresolved questions about where her works truly belong. Hilda Trujillo Soto, who spent nearly two decades guiding the Museo Frida Kahlo in Mexico City, better known as the Casa Azul, has come forward with an extraordinary disclosure. She has raised concerns that several artworks believed to be part of the museum’s collection may be unaccounted for, and some appear to have surfaced in private hands.

“I am driven by a commitment to the care of artistic heritage and to the transparency of museum administration..." — Hilda Trujillo Soto, Former Casa Azul Director

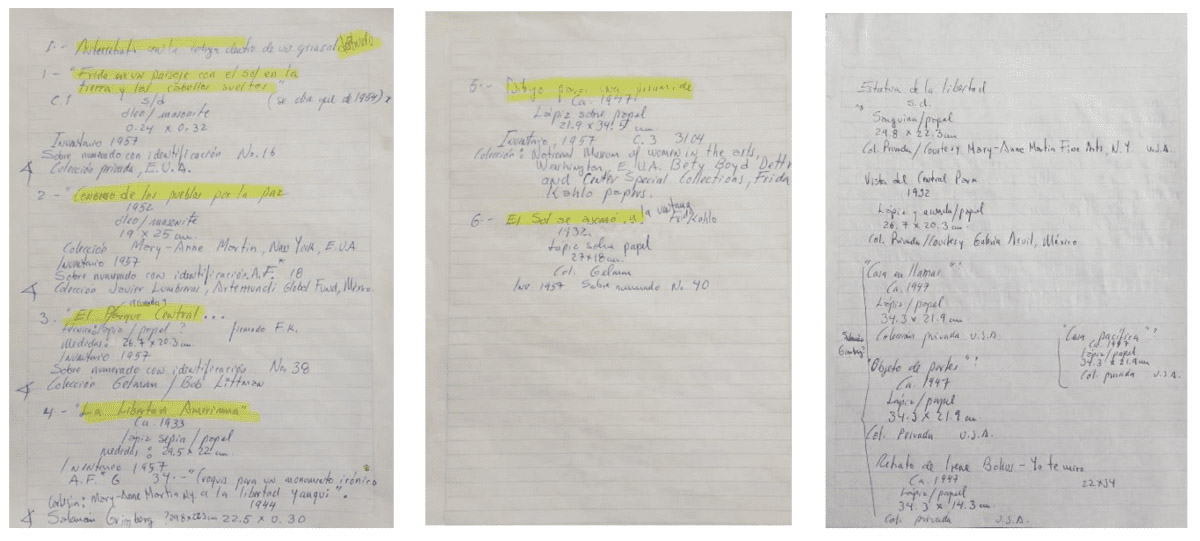

In a blog post published April 2025, Trujillo Soto recounted long-standing concerns she encountered during her tenure, first as deputy director and later as director of the museum from 2002 to 2020. She described signs that certain works by Kahlo had quietly disappeared from the museum’s inventory, only to later appear in auction catalogs or international exhibitions.

“I am driven by a commitment to the care of artistic heritage and to the transparency of museum administration,” she wrote. Her aim in going public, she explained, is not to place blame but to prevent further loss and encourage renewed attention to how Frida Kahlo’s legacy is being preserved. She hopes the discussion might inspire reconnection with works that have since left the institution, whether through collaborative loans, extended exhibitions, or private-public partnerships.

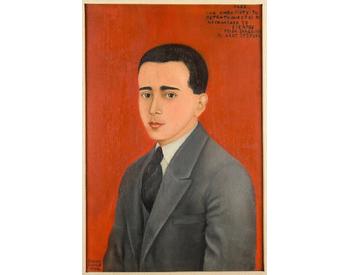

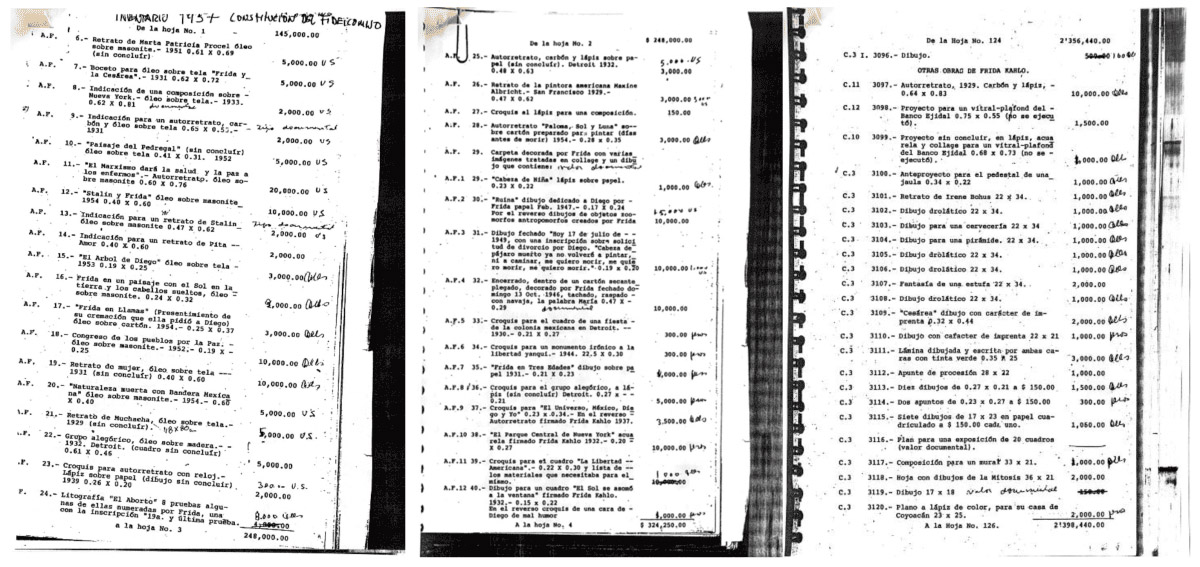

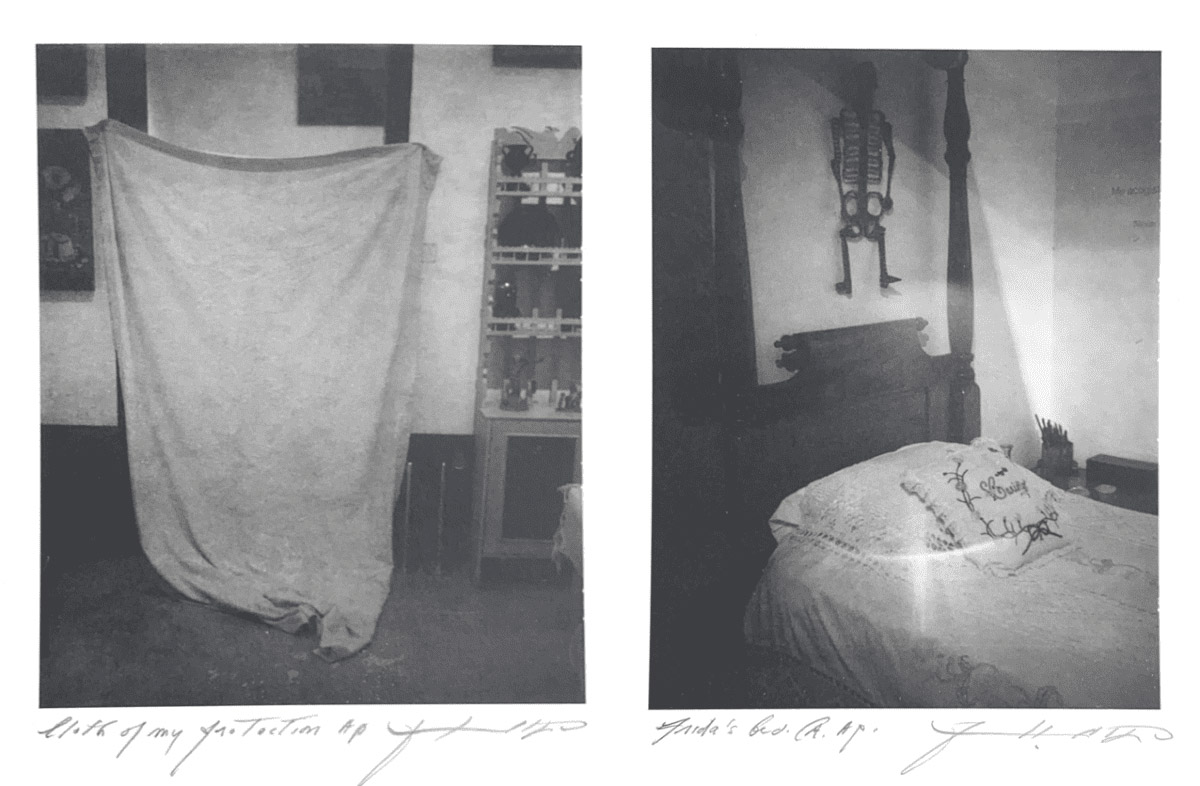

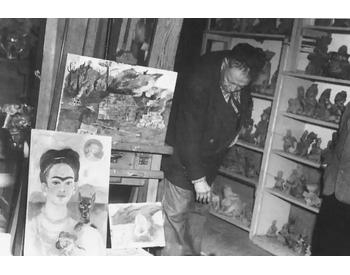

When Kahlo died in 1954, her husband, Diego Rivera, envisioned their estate as a cultural gift to the nation. In the final years of his life, Rivera worked to compile a complete inventory of their shared belongings and artworks. These were to be preserved and administered by the Diego Rivera Anahuacalli Frida Kahlo Casa Azul Museum Trust, now overseen by the Banco de México. That trust was designed to protect the legacy of two of Mexico’s most influential artists and to ensure public access to their personal and artistic worlds.

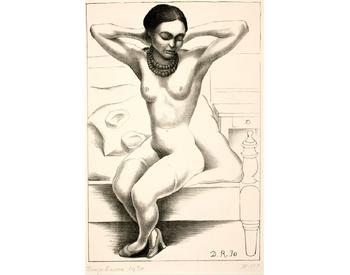

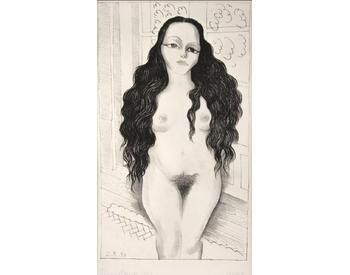

As Kahlo’s reputation has grown into a global phenomenon, the movement of her work across borders and generations has become more complex. Over the decades, some pieces that may once have been linked to Casa Azul have found their way into private collections, where they are often well cared for and deeply respected.

Rather than igniting controversy, Trujillo Soto’s message opens a broader and more hopeful conversation. It invites private collectors and institutions alike to consider new possibilities for collaboration. With growing interest among collectors in lending significant works to museums, this moment presents an opportunity to bring Frida’s art back into public view, even if temporarily. Her voice has always transcended location, speaking across time and space with enduring power. What matters most is that her work remains visible, accessible, and engaged with by new generations.

If any works have quietly transitioned from museum records into private holdings, whether through sale, inheritance, or archival oversight, Trujillo Soto’s message serves as an invitation rather than an accusation. It is a call for stewardship and shared responsibility. By encouraging the return or lending of such pieces, Casa Azul could further its mission as the living heart of Kahlo’s legacy and foster deeper partnerships with those who hold her work today.

Frida Kahlo’s story has always been one of resilience, reinvention, and radical honesty. Her art deserves the same. This could be a moment not of loss, but of reconnection.

Ready to collect works by Frida Kahlo?

We offer end‑to‑end expertise - acquisitions, legacy planning, and collection development - so every artwork adds cultural depth and financial strength. Let's shape your collecting future.Book your consultation now!